Cheap Dopamine vs Real Dopamine: What Your Brain Actually Craves

What is cheap and real dopamine?

Dopamine is being misunderstood as always being the pleasure hormone. In neurobiology, it is more accurately depicted as the motivational neurotransmitter.

It doesn’t just provide a sense of happiness and pleasure. It activates reward prediction, reinforcement learning, and goal-oriented behavior.

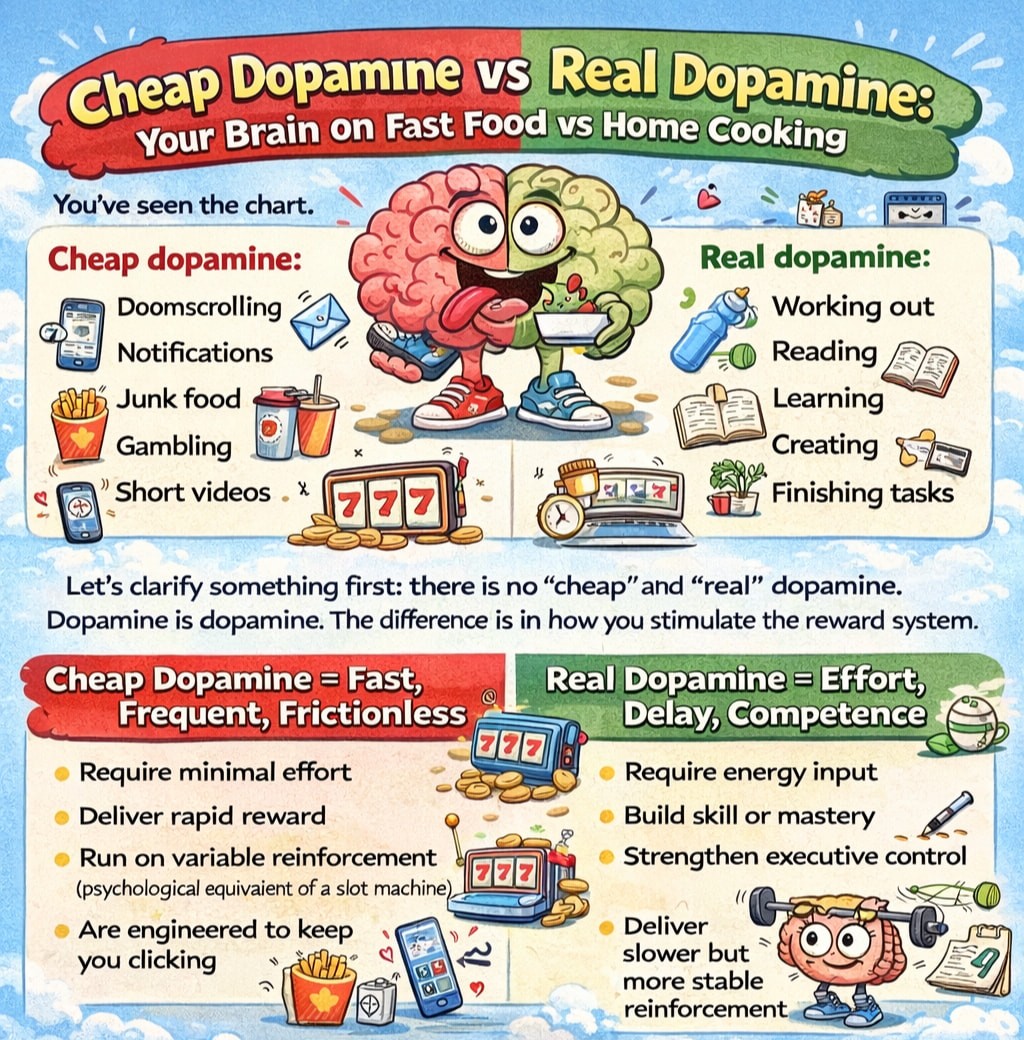

There is no differentiation at the molecular level when we talk about cheap and real dopamine. It refers to the amount of effort required to attain the release of this substance.

Understanding this difference is critical for long-term productivity, mental health, and behavioral resilience.

Dopamine, also known as 3,4-dihydroxytyramine, is a neurotransmitter that is produced primarily in:

Ventral tegmental area (VTA)

Substantia nigra

Hypothalamus

Key pathways include:

Mesolimbic pathway – reward and reinforcement

Mesocortical pathway – cognition and executive function

Nigrostriatal pathway – motor control

Activation of canonical dopamine neurons has a rewarding effect—it increases the frequency of actions that lead to their activation

‘Cheap dopamine’ refers to high-frequency, low-effort, instantly gratifying stimuli that result in a burst of dopamine release without any delay

Watching reels

Eating junk food

Winning lotteries and games

Online shopping

These activities:

Produces a rapid and excessive dopamine surge

Requires minimal to no effort

Develops a sense of dependence and addiction

Over time, repeated high-frequency stimulation can lead to:

Reduced dopamine receptor sensitivity (downregulation)

Increased tolerance for dopamine release

Decreased motivation

Impaired focus

Reduced memory power

“Real dopamine” refers to dopamine release generated from effort-based, goal-oriented, meaningful activities.

Excercising

Reading books

Completing tasks

Creative works

These activities

Produce Moderate but adequate dopamine release

Requires some amount of effort to obtain dopamine release

Strengthens long-term reward system

Improves functioning and creative mindset

Improves focus

Activates hippocampus to store activities as long-term memories.

Promotes sustained motivation

Cheap Dopamine | Real dopamine | |

|---|---|---|

Reward timing | Immediate | Delayed |

Efforts required | Minimal to none | Moderate to high |

Sustainability | Low | High |

Frequency | High | Low |

Motivation | Decreased baseline of motivation | Builds long-term drive |

Outcome | Short-lived pleasure | Long-lasting satisfaction |

The problem is not when it occurs occasionally. When continuous long-term exposure to such dopamine occurs, it leads to

Increased procrastination

Reduced attention span

Anhedonia (reduced ability to feel pleasure)

Higher impulsivity

Decreased tolerance for discomfort

Everything feels dull

Requires an excessive amount of dopamine release to feel even a little gratification

Constant dependency and addiction to cheap Dopamine activities

Some may even end up with withdrawal symptoms if left unnoticed.

Recently, the term ‘Dopamine fasting’ or ‘Mind detox’ has gained popularity. It refers to temporarily avoiding such cheap-dopamine activities to rewire the brain to function normally.

Though it cannot be a permanent solution, it could help to reduce overstimulation and promote long term effects if done correctly.

Instead, you should try to

Reduce high-frequency reward activities

Effort-based reward

Normalize discomfort

Cheap dopamine is engineered for repetition. Real dopamine is earned through effort, progress, and mastery.

The long-term health of your reward system depends not on eliminating pleasure, but on balancing instant gratification with purposeful challenge.

If your baseline motivation feels low, examine not your ambition, but your inputs.

Salamone, John D., et al. “Mesolimbic Dopamine and the Regulation of Motivated Behavior.” Behavioral Brain Research, vol. 137, no. 1–2, 2002, pp. 3–25. Elsevier, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0166432802002359.

Berridge, Kent C., and Terry E. Robinson. “What Is the Role of Dopamine in Reward: Hedonic Impact, Reward Learning, or Incentive Salience?” Brain Research Reviews, vol. 28, no. 3, 1998, pp. 309–369. Elsevier, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165017398000195.

Hamid, Anna A., et al. “Mesolimbic Dopamine Signals the Value of Work.” Nature Neuroscience, vol. 19, no. 1, 2016, pp. 117–126. Nature, https://www.nature.com/articles/nn.4177.

Gardner, Matthew P. H., et al. “Rethinking Dopamine as Generalized Prediction Error.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B, vol. 285, no. 1891, 2018, https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspb.2018.1645.